Takeaways from “A Conversation with the Godfathers of Graffiti"

Soot, stencils, Zorro, and the role of muncipal workers in art.

Graffiti is not Arte Agora, but the rise of graffiti as an accepted art form over the last 40 years has spurred more and more artists to put work outdoors. They are critical precursors to our work in defining the genre.

While we were in Los Angeles last week we caught two events put on by Beyond the Streets, the leading publisher and exhibitor of street art. One was an opening of the Gordon-Matta Clark show at Control Gallery.

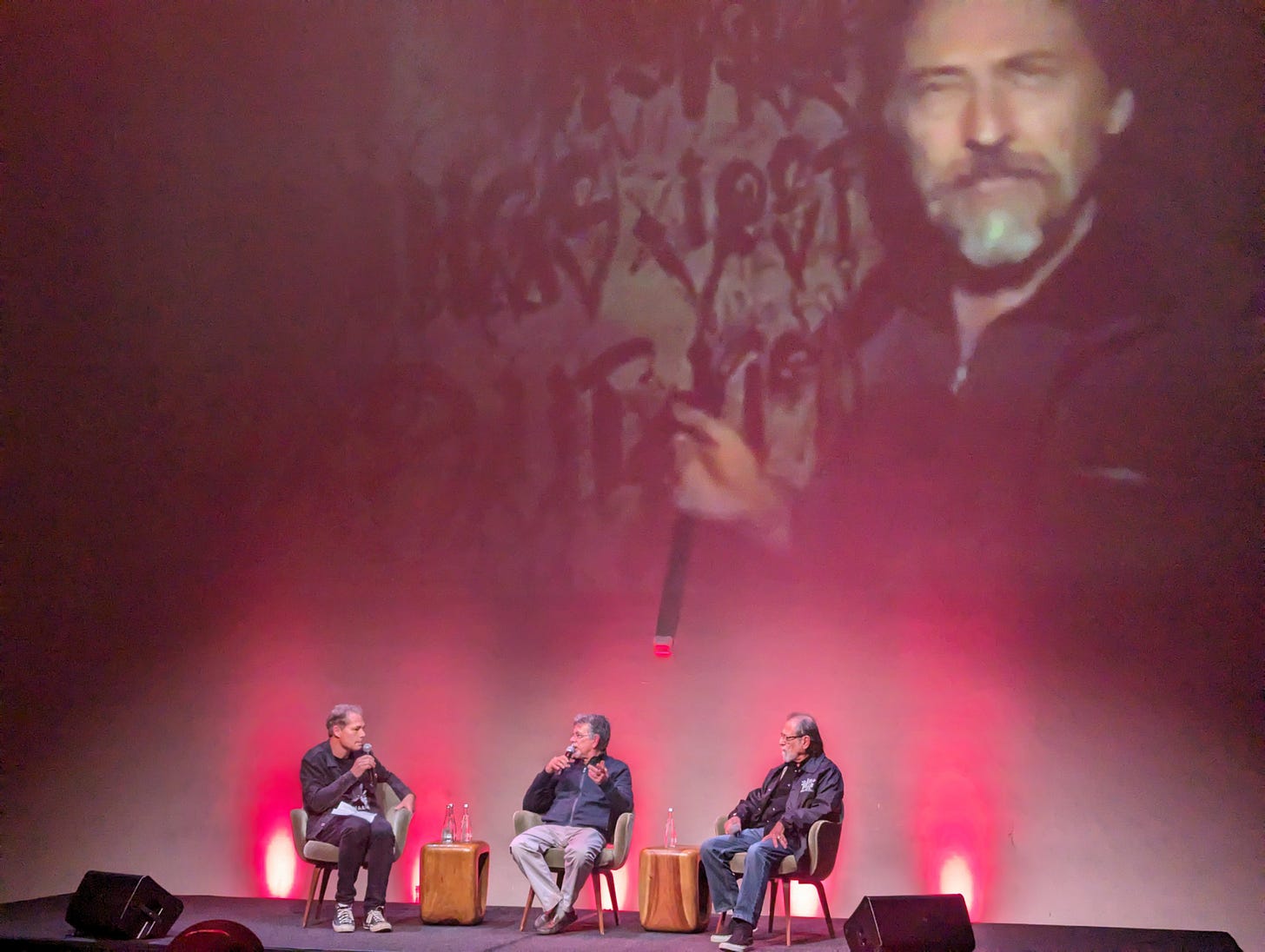

The other was “A Conversation with the Godfathers of Graffiti”. The discussion between Chaz Bojórquez and Taki 183 at Neue House was moderated by Shepard Fairey. Beyond The Streets founder Roger Gastman noted that this was the first time that the key figures from the East and West coast had really sat down for an extensive talk.

Given his relative fame, Fairey was a gracious and respectful moderator. He added his own take and had great questions. Here’s takeaways:

Soot on tunnel walls

In the early 1960s, Chaz would play in the drainage tunnels along the Arroyo Seco River in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. There was four and a half feet of water and he and his friends would wear “two or three layers of Levi's” then slide & spin on the green moss.

Looking up, he’d see graffiti from the 1940s and 50s— block letters formed from the soot of candles (the tunnels were pitch black otherwise) and the kerosene from zippo lighters. Chaz admired the people who wrote their names and a date— this was his first exposure to tagging.

Chaz’s first stencil

Chaz spoke of how he designed his first stencil. He would visit his grandparents in Tijuana and he would see stencils representing the two political parties— the PAN and the PRI. These were very simple, one color, three-letter stencils that could be thrown up on a wall fast. Speed is key. Later, in part as a response to the racism he encountered, he wanted to create an image that represented and in order to assert his own identity, he wanted to create an image that he could use to represent him and could also be fast.

His design combined the Día de los Muertos skull, a “big daddy hat, a fur collar from New York”, and zoot suitors from Mexico. He said, “so that was kind of like this symbol that represents Hollywood. New York, and Latino. Yeah, that's cool. I like that— that's me. So that’s how I made the stencil. That was 1969”.

Taki’s name

Fairey asked Taki about the origin of his tag. “My name is Demetrius, which is Dimitri in Greek”. He says that it is common in Greek to add the diminutive “-aki” suffix to a name in order to express endearment and differentiate. Dimitri turns into Dimitraki, Kosta becomes Kostaki, and so on. Often it’s shortened to just “taki” “My mother called me that; everybody called me Taki. So that’s where it came from. The 183 came from the street”. He spoke of Julio 24, one of the first taggers to put a street number in their name. “But we don't know what it was. We thought on July 20th, at four o'clock, something would happen”.

The role of Zorro

Taki was asked about what drove his desire to tag and he mentions the desire to be everywhere and anonymous at the same time. “When I was a little kid here, we used to watch Zorro. The guy, he was like a social avenger basically. He’d do his stuff, take the money from the rich guy, and at the end, he’d do a big Z on the wall. And nobody knew who he was, because he wore a mask. So that, I guess that got me, as a little kid— to do it but nobody knows how you do it. That's what really started me”.

Hollywood scale

Chaz agrees. “First I want to say Zorro was the first tagger”. He goes on to note a main difference between New York and LA, which is scale. “We are so Disneyland-oriented over here. It was easy to go big scale because of what is in the movies. I thought Fantasia was the first graffiti movie”.

He goes on: “I started tagging and actually put my name on there with my stencil because I wanted to be in your face— that was my attitude— just to really get up in your face and put it on me.

He says that he knew about Taki and others in part because people sent him clips from the Village Voice. When he saw what was happening with subways in New York, he immediately thought of the freeways as his canvas where he could get scale and audience at the same time. Also: and “I had the idea that it's public space, so it's not a crime.”

The role of municipal workers

Fairey asked Taki if his parents knew what he was up to. “After a while, they figured it out from the black fingers from the markers and They figured I could be doing worse things so they didn't say like, “don't do it anymore”.

When asked about the Ed Kock-era crackdown on graffiti, Taki references a neighbor who worked in the Mayor’s Office. The impression at the time was that “if Koch’s hair was on fire” the neighbor / staff member would say, “ah don’t worry, he’s just a kid, this will all go away. So he was like my rabbi”.