Who is the custodian of Arte Agora?

The slippery slope of “ownership” for art placed in the public way

Brian Donnelly, known as the artist KAWS, was profiled last week in The New York Times about the art he chooses to collect and his collection that has over 4000 pieces. KAWS called his practice of collecting “custodianship” because he doesn’t feel like a piece of art is really his. “I’m just sharing this time with it, then passing the baton.”

A former practitioner of Arte Agora (art that is made, placed or sold in the public way), KAWS notes in the NYT, that he sometimes buys back his own pieces, particularly those he created by taking advertisements from public phone booths (remember those?), painting over the ads, and then slipping them back into the frames of the phone booth.

It is not uncommon for artists to do what KAWS did: take material that’s in the public way and alter it. The pics below are of bus shelter hacks by a Chicago-based artist, known on Instagram as @one_773. He removed the bus shelter advertisement, created his own art, and then “returned” the piece to the bus shelter. (As our local bus shelter advertising leans further into digital, we’ll lose the opportunity to experience artwork like this.)

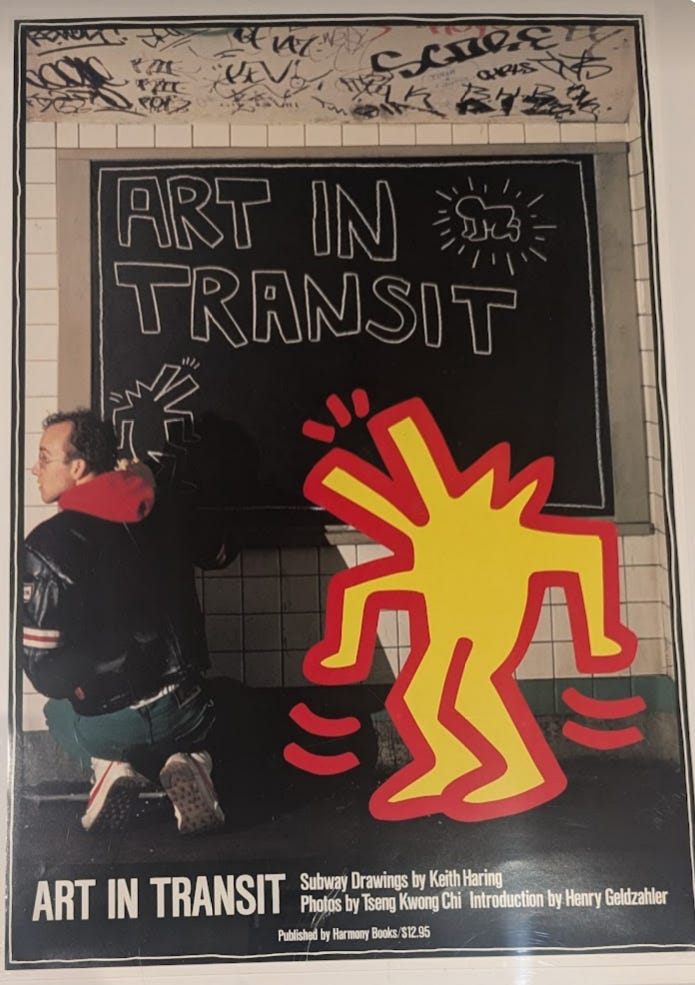

Early in Keith Haring’s career, he too had an Arte Agora practice. He drew on blank ad spaces, which were covered by black paper in the New York subway stations. And later this month, Page Six reports (h/t, Francine L.), art collector Larry Warsh is working with Sotheby’s to auction 31 Haring subway drawings that were clearly removed by someone.

Which brings us to the salient question at hand: who “owns” the art placed in the public way? The artist has chosen to put it out there, to share their work with the public in public space. What happens to it once it’s out there?

KAWS had this to say regarding his own pieces of Arte Agora: “I didn’t even think of them as something I own. You know, I just thought of them as serving a purpose of putting work out in the street.”

The custodial or, preservationist instinct—to remove these pieces of art—is the only way to “save” them from destruction and disappearing. Larry Warsh tried to peel off some of those Haring subway pieces in the 1980s, but they ripped. So, he came into possession of those 31 Haring pieces because he bought them from somebody who removed that artwork from the public way, and now it will be auctioned by Sotheby’s on November 21.

As Dan asked in his essay on the Keith Haring show “Art is for Everybody,”

“Why can't people take the pieces? Why can’t other artists 'collaborate' with the existing piece? Why can't ephemerality be caused by an actor other than the advertiser or the MTA performing an intervention? Why doesn’t 'everybody' explicitly include all actors in the public way?”

Haring used material without authorization that didn’t belong to him to create something that he considered his. But as we’ve pointed out repeatedly in our books about Arte Agora, there are multiple actors in the public way, including artists, art appreciators, municipal buffers, national advertisers, construction workers, scaffold assemblers, and passersby.

Dan and I are actors in the public way, and we have 100s of pieces of Arte Agora. We have personally peeled these off of construction sites, barricades, street signs, lampposts, etc. As custodians of this artwork, we will return any and every piece to the artist if they want it back.

If someone, hadn’t “rescued” Haring’s work, it would have been lost to the public. It would only be a memory. Mere ephemera. We would have lost a part of our history of art in the streets. And then, where would it be?

Simply forgotten history.